The Differences Between APIs and Messaging for Application Communication

Phil Wilkins | Cloud Developer Evangelist | December 14, 2022

Software needs to talk to other software. Sometimes software in one part of an application needs to request services or exchange data with another part of the application. Or, one application has to request services or exchange data with an entirely different application.

There are two typical mechanisms used for these types of communication: application programming interfaces (APIs) and messaging.

The differences between APIs and messaging can sometimes become confusing. That’s because the terms are thrown around in a lot of ambiguous ways. The acronym API itself does have an explicit meaning, but for reasons we’ll explain below, the term has taken on several different meanings. Messaging is a term often used very loosely to cover almost any system-to-system communication. So, let’s clarify what is really meant by APIs and messaging.

A Detailed Definition of APIs

Broadly speaking, an API is the contract that defines how that software can receive and respond to service requests. That contract is set by the software’s developers.

Sound simple? It is, at one level. In practice, the implicit meaning of API can change based on the subject of the conversation. If we unpack the acronym, an API is about the interface or “contract” by which one piece of software can interact with another piece of software. Sometimes the conversation about an API is focused on its high-level architectural definitions; sometimes it’s very granular, detailing the specific ways developers implement the API.

Some books and articles about APIs use the analogy of an API being a door, with the API’s characteristics describing the door. For example, it could be a grocery store door that automatically opens or an ultra-secure bank vault door. An application’s contract—the door characteristics—should help address considerations such as:

- What does the API do, at a high level? In our door analogy, does it open without needing the guest to stop and touch something (grocery store door) or does it control access and protect what is behind the door (bank vault)?

- What payloads (data being transmitted) will it need to support to let the software perform? For example, the software might receive a bank account number and a security authorization and reply with the balance in that bank account.

- What data is to be exchanged in order to perform that service? For example, it’s important to define exactly what a valid account number and security authorization look like and to define the contents of the response. Details matter here; ambiguity can lead to errors.

- What’s the address of the door? This typically means how the universal resource identifier (URI) for the request is formed. That is, how does the requestor actually talk to the API?

- Which protocol(s) will be used to communicate? These can range from well-known technologies, such as HTTP and FTP, to special protocols, such as STOMP and QUIC.

- What terms and conditions must the API user adhere to? These can include encryption details, a limit on how often the APIs can be called, or charge-back mechanisms for commercial services.

- What promises does the API make? These might include service-level guarantees for the API, such that a request will be acknowledged or performed within a specific time period.

Defining Messaging in Application Development

While APIs define the terms for how software will send and receive service requests, messaging is the process for sending information from one system to another. The key word is process.

Think of it this way:

-

Messaging refers to the process of transmitting some chunk of information—the message—from the service requestor to the service provider (often using a third party known as a broker).

To use real-world analogy, consider a company sending a text message to a customer. The service provider has to know the recipient’s phone number so that the mobile carrier can deliver the message. The payload itself, however, can be anything from the carrier’s perspective. The carrier doesn’t need to know if your text message is in English, Spanish, Japanese, or an emoji.

-

Messaging refers to all the behind-the-scenes action of getting that message from the sender to the customer.

You and your customer don’t need to understand how the messaging process works; you’re trusting that the carriers and smartphone makers have done their job properly. And likewise, the carrier doesn’t need to understand the payload; they simply need to ensure that it is delivered to the right person and isn’t garbled or distorted.

It is worth reiterating that most messaging platforms are unconcerned about the payload as long as it fits within the constraints of the technology. To return to our analogy, the smartphones and mobile carriers don’t care whether your text is English or an emoji.

See more detail about the composition of APIs, API platforms, and API management.

APIs and Messaging Work Together in Enterprise Systems

Enterprise software systems are built from multiple, separate executable processes and, as a result, require interprocess communication (IPC). The communications here can be complex, requiring many back-and-forths with many API calls with a lot of strictly formatted data, to carry out a transaction. Those transactions have to be carefully orchestrated and completed in the right order to meet a business need.

For example, think of a customer purchase order. The process will need to access the customer database; query the inventory database, the accounting system, an invoice-generating system, and the credit card charging system; adjusting the inventory and the customer account; creating a warehouse request; and originating a shipping request—all of these must be done in the right order and completed correctly.

Historically, these interactions were done using some form of shared storage, such as a file system or a database. However, in more modern enterprise systems, the processes can communicate directly with each other, speeding up the process and removing issues (such as when the stock for your order has already been allocated by previous orders).

Synchronous and Asynchronous Behavior

We can characterize our communication as synchronous or asynchronous in nature. Synchronous communication means that all the parties involved in a communication must be present and able to resend. In our ordering example, the systems involved in electronic payments must be available for real-time interaction. In other cases, the communication can be asynchronous, allowing the parties of systems wanting to communicate not have to be present at the same moment. That’s how it works when we write emails to each other. For a communication to work asynchronously, we do need an intermediary to be involved to enable the passing of information back and forth.

These complex enterprise-messaging systems come in different varieties or patterns:

-

Service bus. The service bus acts as the glue between different processes and performs orchestration between those processes, such as in the complex transaction mentioned above. Service bus systems typically incorporate value-added features, such as the ability to translate payloads from one format to another (English to French in our text messaging analogy), route messages based on the message content, or even make some decisions based on the state of the complex transaction. For example, tasks A and B can be done in parallel; do task C if task B is completed successfully; if tasks B fails, do task D; if task D fails, get human intervention.

Service bus–style messaging is sometimes described as using a smart pipe, because of that added intelligence in terms of messaging routing and scheduling in the “pipe” between the providers and consumers. That is also referred to as orchestration.

![Service bus diagram, description below]() The message provider calls the service bus supplying a message. The service bus then takes the message and routes it to the consumers. During the routing, the message may be subject to transformational logic and filtering.

The message provider calls the service bus supplying a message. The service bus then takes the message and routes it to the consumers. During the routing, the message may be subject to transformational logic and filtering.A synonymous term for service bus is message bus. When these technologies were first evolving to become service-oriented architecture (SOA) solutions, there were some differences between message buses and service buses. Today, there are no real differences. In fact, the name is increasing shortened to merely bus.

-

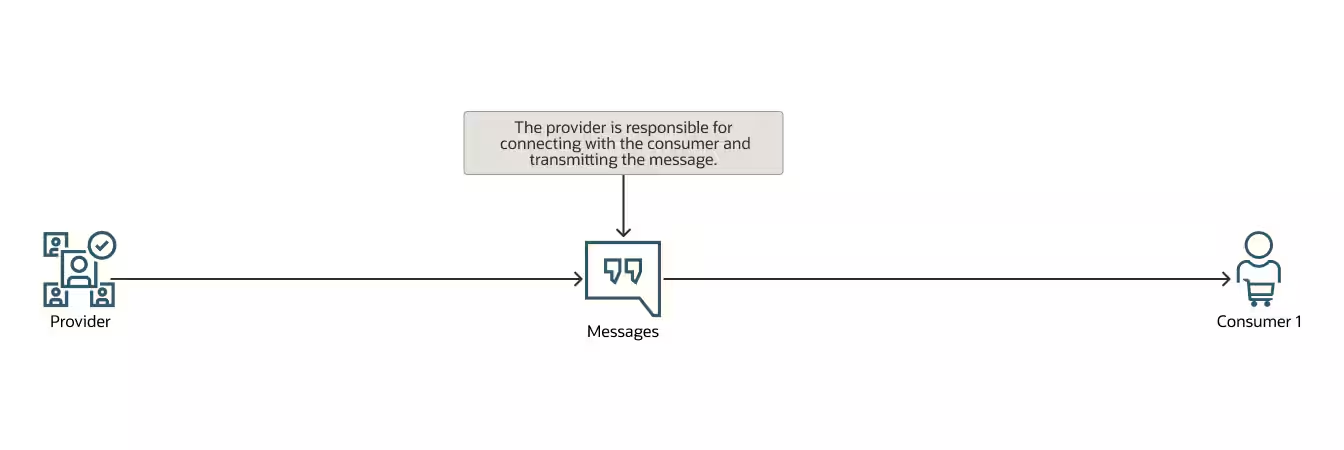

Web services:In the broadest sense of the term, web services represent direct synchronous communications between two processes, typically using the TCP and HTTP protocols (or variations, such as HTTPS and HTTP/2). The consumer and client are realized as point-to-point connections (although it is common for the provider end to support multiple concurrent client connections). There may be proxies (from network firewalls to API gateways, and web caches) and network (switches and routers) intermediaries between the two processes, but neither the provider nor the consumer will be aware of them.

![Web services diagram, description below]() The message provider communicates directly with the consumer. The transmission process is dependent on both parties being available.

The message provider communicates directly with the consumer. The transmission process is dependent on both parties being available. -

Message brokers:Message brokers are intermediaries between the message provider and the message consumer and have commonalities with both service buses and web services.

Brokers reside between the sender and receivers of the messages and will receive the message being communicated and store it until the recipients have consumed it. This means that the message being transmitted can be done without worrying about the recipient’s immediate availability. As a result, this kind of communication is often described as asynchronous or “fire and forget” because you can be assured that the message should be delivered at some point, as long as the broker remains operable.

The similarity to web services comes from the fact that the connection between the client and broker is represented as a point-to-point connection; the message broker is functionally invisible.

The resemblance to a service bus comes from the fact that the broker offers a value-added service, in that it can hold the received messages until the recipients are available. Unlike a more robust service bus, a message broker has minimal intelligence other than understanding simple things, such as knowing which destinations may want to receive a particular message and what to do if the destination doesn’t consume the message in a timely manner.

A brokered communication style is described as having a dumb pipe. Because the brokers have minimal intelligence, and it requires the endpoints to understand what is needed when a message needs to be sent or received. This style is described as choreography (as opposed to the more intelligent orchestration of a service bus).

![Message brokers diagram, description below]() The message provider gives its message to the broker. The broker then holds the message until the consumer(s) have either requested a message or are able to receive the message. The provider is not dependent on the consumer.

The message provider gives its message to the broker. The broker then holds the message until the consumer(s) have either requested a message or are able to receive the message. The provider is not dependent on the consumer.

The Role of Streaming in Enterprise Messaging

For this discussion, streaming can be seen as a rather specialized form of messaging, although some streaming technologies can support an element of data processing. Streaming, in this context, describes the act of sending a continuous flow of events through the IPC technology to the same destination(s) regardless of whether web services or message brokers implement the communications. (Very rarely are service buses involved, because there’s too much data, flowing too quickly, for a service bus’s extra intelligence to be needed.)

In addition to the continuous flow of data in a stream, streaming usually expects a near real-time or low-latency connectivity. This won’t be a surprise when you consider the fact that services, such as Netflix, are traditionally referred to as video streaming. You certainly don’t want video content to stop and start while new bits of video are sent from the provider or while a message broker transforms video from one format to another.

Common technologies for web service streaming are WebSockets, gRPC streams, and GraphQL subscriptions. When it comes to brokered messaging streams (using technologies, such as Kafka), you can sometimes leverage how the broker works to look at a “slice” of the transmitted events. This helps you gather valuable insights, including information about the stream itself—hence the term streaming analytics.

While the logic applied in streaming analytics may be sophisticated, the message broker does not perform decision or message manipulation; that’s why the broker is still be considered dumb. These sorts of streaming analytics capabilities are often implemented with technologies, such as Kafka Streams.

API and Messaging Industry Standards

APIs and messaging systems are simple to describe, but very complex in the details and technical characteristics. There is simply no room for ambiguity, which leads to a real need for accurate industry standards and documentation and ideally the best application of these standards.

This has been an area of development, particularly for APIs, for more than ten years. The industry has embraced the OpenAPI specification for REST-based APIs, which are a form of web services—and probably the most common types of APIs used in modern enterprise software.

With APIs (and streaming) there are a number of additional standards for defining and describing aspects of the messages and their transmission. These include protocol buffers (also called Protobuf and used with gRPC) and, more recently, GraphQL, JSON Schema, and YAML.

In the asynchronous messaging domain, the last few years have seen successful efforts to coalesce around a definition called AsyncAPI, which has adapted ideas from OpenAPI and other evolving standards to address the many messaging requirements.

Modern distributed applications are implemented as a collection of services that are separate pieces of software, sometimes running on the same servers, sometimes not. APIs provide a way for those pieces of software to talk to each other in order to request services or to exchange information. Messaging systems provide the infrastructure to facilitate asynchronous communications and provide intelligent middlemen for API calls, which may be very simple (the way that smartphone texts work) or extremely complex (such as the orchestration for complex multistep business transactions). Not to mention the distributed services communicating directly with each other using APIs. Fortunately, evolving techniques and standards allow for the use of APIs in everything from database calls to streaming media. And those APIs and messaging standards continue to evolve and advance, making the transition to modern distributed software architectures faster, easier, and more secure.